Depression Through a CBT Lens: Making Sense of the Fog

Depression often feels like being stuck in a loop you didn’t choose, one that quietly drains energy, sense of connection and confidence. Understanding how that loop works can be the first step in shifting it.

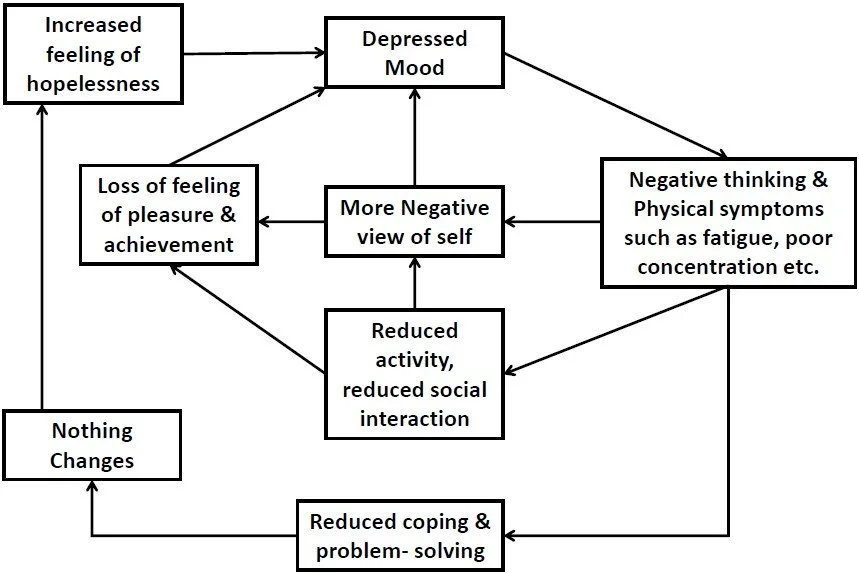

Depression can affect our mood, motivation, sleep, relationships, work, and the sense of who we are. People often describe it as feeling “stuck”, “foggy”, “heavy”, or like their brain has “lost its spark”. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) offers a practical, research-based way to map what’s happening inside the loop. Rather than seeing depression as a personal flaw, CBT views it as a self-reinforcing cycle between thoughts, emotions, body states, and behaviours.

How CBT Conceptualises Depression

The CBT model of depression, first outlined by Aaron Beck and refined by Westbrook et al. (2007), illustrates how difficult experiences activate our core beliefs (“I’m not good enough”), which trigger automatic thoughts, emotional pain, and behavioural withdrawal. Each step feeds the next step in the chain until life shrinks into something we barely recognise and often can’t find a way out alone.

Typical CBT cycle:

Trigger: loss, conflict, chronic stress, or burnout, usually started by something outside of our control.

Thoughts: “What’s the point?” “I’m failing again.”

Emotions: sadness, guilt, shame, numbness.

Body: fatigue, heaviness, changes in sleep or appetite.

Behaviour: withdrawal, avoidance, shutdown.

Consequence: reduced connection and activity, this reinforces the feelings of hopelessness.

CBT recognises this as a protective system gone rigid, rather than seeing it as a weakness or laziness. The common misconception about CBT is that is “positive thinking,” but understanding the system as a whole means we can see that small, targeted changes can begin loosening its’ grip on our lives.

Why We Might Use This Model

Understanding depression as a cycle rather than a flaw changes everything:

It reduces shame. You’re not broken; your brain is doing its best to protect you.

It increases choice. Once you can see the pattern, you can decide where to interrupt it.

It builds agency. Small, realistic steps can restore momentum and hope.

Modern research supports this conceptualisation: CBT reliably reduces depressive symptoms across mild-to-severe cases, with sustained benefits in relapse prevention.

How CBT Informs Treatment

CBT treatment follows the same logic as its conceptual model, intervening at the weakest points in the cycle to try and restore movement in the smallest ways.

Behavioural Activation: Reconnecting With Life

When motivation disappears, CBT starts with behaviour, not thought. Clients identify small, meaningful actions that gently re-engage pleasure, purpose, or connection:

A two-minute walk in sunlight.

One message to a supportive friend.

Preparing a simple meal.

Each action provides feedback that life can still offer reward, countering hopeless predictions.

Working With Thoughts (Not Against Them)

CBT helps us notice and question habitual thoughts with curiosity:

· “Is this thought a fact, or a feeling?”

· “Would I say this to someone I care about?”

Rather than forcing positivity, gentle curiosity builds cognitive flexibility, seeing more than one possible interpretation of the events. Compassion-focused techniques aim to soften our harsh inner dialogue.

Regulating the Body and Emotions

Depression affects our nervous system as much as the mind. Modern CBT incorporates skills from mindfulness-based and dialectical behaviour therapies: paced breathing, grounding, sensory resets, and routine stabilisation. For people with trauma, or sensory sensitivities, this might include somatic techniques, or sensory strategies, it’s about working with what works best to calm your body and finding a personalised strategy.

A Trauma-Informed and Neurodiversity-Affirming Approach

We often need to recognise that depressive patterns are often protective. Many of us have come from a past where shutdown (or a “freeze” or avoidance response) may have been kept someone safe. A trauma-informed CBT approach therefore:

Prioritises safety and emotional regulation before cognitive work.

Uses language that validates survival responses.

Frames therapy as collaboration, not correction.

CBT in this format can focus less on pathologising or unhelpful thoughts as “distorted thinking” and hightlight strategies that are structured around energy pacing, executive supports, and self-compassion. Visual tools, concrete examples, and micro-steps enhance accessibility.

What the Research Shows (2018 – 2025)

CBT and Behavioural Activation remain first-line psychological treatments for depression.

Digital CBT (iCBT): Guided online programs show significant, sustained symptom reduction, supporting access for many people without having to attend in person therapy.

Limitations: There have been some challenges for people with chronic or trauma-related depression.

Putting It Into Practice: Gentle Everyday Experiments

These small, evidence-based steps can help interrupt the depression loop, safely and compassionately:

Focus Area

You don’t need to overhaul your life to start shifting depression’s cycle. Small, realistic actions can create meaningful change over time.

Start with your body, a short stretch, a quick shower, or simply stepping outside for two minutes. These brief movements help re-engage your physiology, reminding your brain that it’s safe to wake up and reconnect.

Next, work with your thoughts. Try naming them gently, rather than believing them outright. For example, when you catch yourself thinking, “I can’t cope,” you might say, “That’s my ‘I can’t cope’ story showing up.” This small shift creates a little space between you and the self-critical voice, allowing room for kindness and perspective.

With emotions, start by naming what you feel, even if the answer is “numb” or “flat.” Research shows that simply labelling emotions can reduce their intensity by around half, helping the nervous system settle and making it easier to respond rather than react.

When it comes to behaviour, schedule one tiny, achievable “win” each day. It might be making your bed, preparing a meal, or walking to the letterbox. These micro-actions rebuild a sense of agency and provide gentle reinforcement that movement is possible, even in small steps.

Finally, remember connection. Depression often urges withdrawal, but even one low-pressure message, a text, a comment online, or a few words to a neighbour, can start to counter the loneliness that deepens low mood.

Each of these steps is small, but together, they begin to loosen depression’s hold, helping your system rediscover safety, rhythm, and momentum.

Addressing Common Critiques of CBT

Some people worry CBT is too structured or “think-positive,” modern adaptions address this by:

Integrating emotion- and body-focused techniques.

Framing cognitive work as exploration, not correction.

Blending CBT with additional techniques including schema, DBT or other therapies as required.

When Life Feels Heavy

Depression is like your brain’s power-saver mode. It shuts things down to conserve energy, but over time, that shutdown keeps you from recharging. CBT doesn’t demand you switch everything back on; it helps you find one switch at a time, rebuilding light gradually.

CBT as a Map, Not a Manual

CBT doesn’t promise instant happiness, it aims to provide a light in the darkness, compassionate map for understanding the path of depression, how it begins, how it loops, and how it can gently change for many people (but not all). It reminds us that mood isn’t a moral verdict; it’s a system, and a signal. When we recognise the pattern that fits, it can help us find the path towards treatment, but the directions need to be flexible enough for every journey. The most important part is that you make the steps your own.